“Paratextual”

May 13 - June 17, 2017

Presented as Samuel Freeman Gallery on La Cienega Blvd, Los Angeles.

Basma Alsharif, Maura Brewer, Juan Capistran, David Horvitz, Shevaun Wright, and Samira Yamin

Paratextual

May 13 - June 17, 2017

Working with text, video, legal contracts, copyright infringement, TIME magazine and Wikipedia entries, these six artists approach and analyze the aesthetic, political, ideological and social manipulations at play in our everyday lives. These artists work to reveal the social constructions that determine how we see, and ultimately read, images and information. Illusions of representation, authorship and individual identity are unveiled. The paratext[1] is laid bare.

The year 2017 has, for many Americans, marked a period of transition. With the proliferation of ‘fake news’ and ‘alternative facts,’ many have begun to question and investigate the information systems that inform and enter our lives. In Basma Alsharif’s Trompe L’oeil, the question of ownership is presented within the language of a carefully constructed still life. Photographs originally taken by T.E Lawrence showing Arabs enslaved by other Arabs are re-photographed and inserted into a scene of uncanny domestic tranquility. Ironically, only one of the images is free of its own copyright.

In The Surface of Mars, Maura Brewer uses Hollywood’s portrayal of the Red Desert of Wadi Rum, Jordan, as an entry point to discuss stereotypical representations of Western women. Using the metaphorical landscape of the Red Desert, Brewer exposes the language of popular feminism in three films where Jessica Chastain plays contradictory leading/supporting roles: The Martian, Interstellar, and Zero Dark Thirty. For Samira Yamin, cutting into images of the Middle East printed in TIME Magazine exposes patterns of representation and challenges traditional Western perspectives regarding the ‘other.’ In her series, Geometries, she cuts delicate Islamic motifs directly into images of violence in the Middle East, resulting in a collision of abstraction and representation.

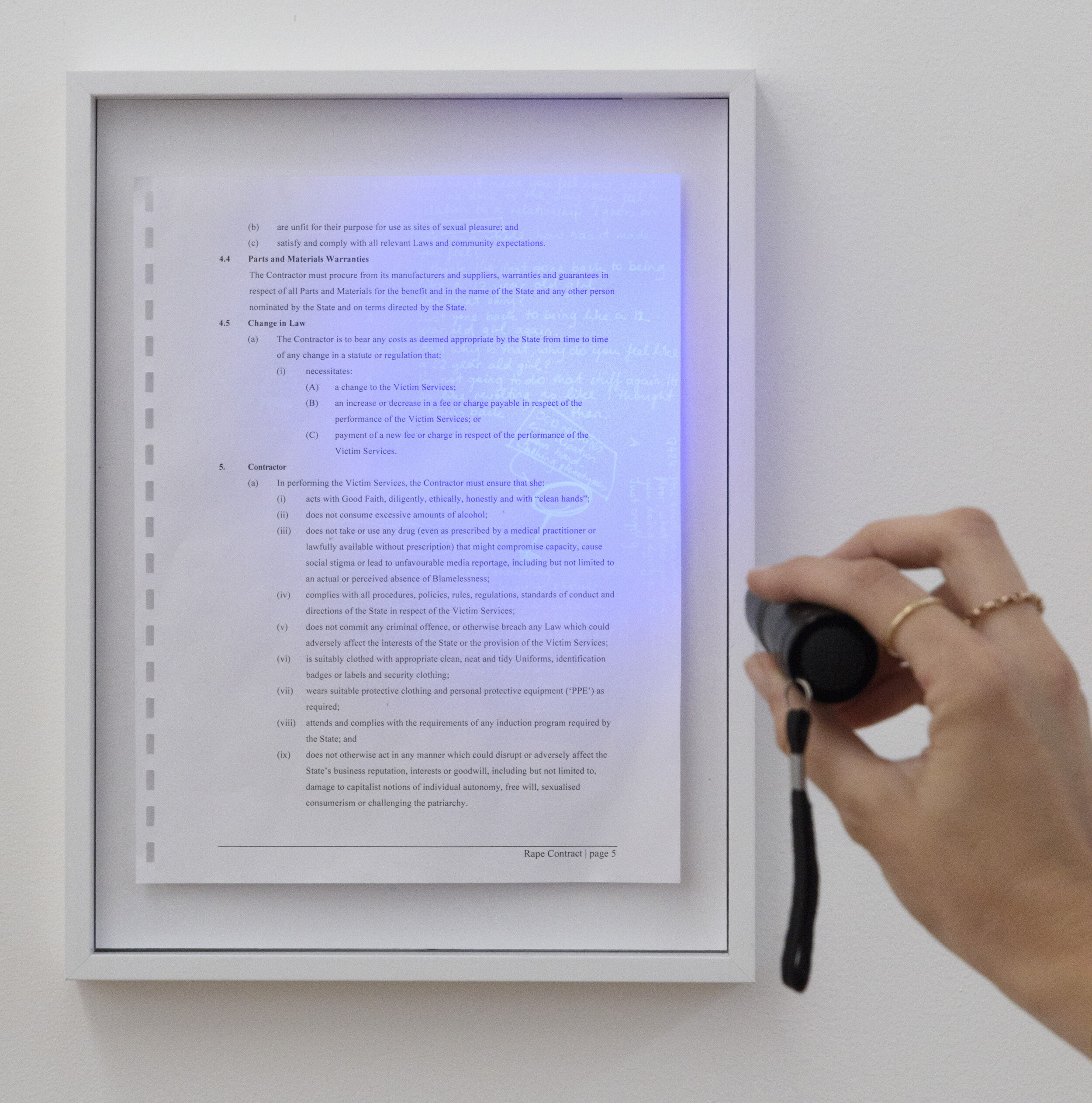

In The Rape Contract, Shevaun Wright reveals the hidden structures that govern law and language by inserting the emotional into the commercial. In invisible ink, the artist includes notes, personal writings, psychiatric reports and a police report taken from a victim of violent rape. These additions can only be seen when the viewer chooses to activate their own role by shining a forensic blacklight provided with the installation. Wright demands that we consider who constructed the language that controls us, whom it is really intended for, and how it determines our actions.

David Horvitz’s Public Access examines the topic of public vs private through a series of ambiguous self-portraits. While visiting public beaches along the California coast, Horvitz photographed himself and then uploaded the images onto Wikipedia entries for those locations. Ironically, the very domain associated with public access -Wikipedia- has since removed these images and banned Horvitz from posting.

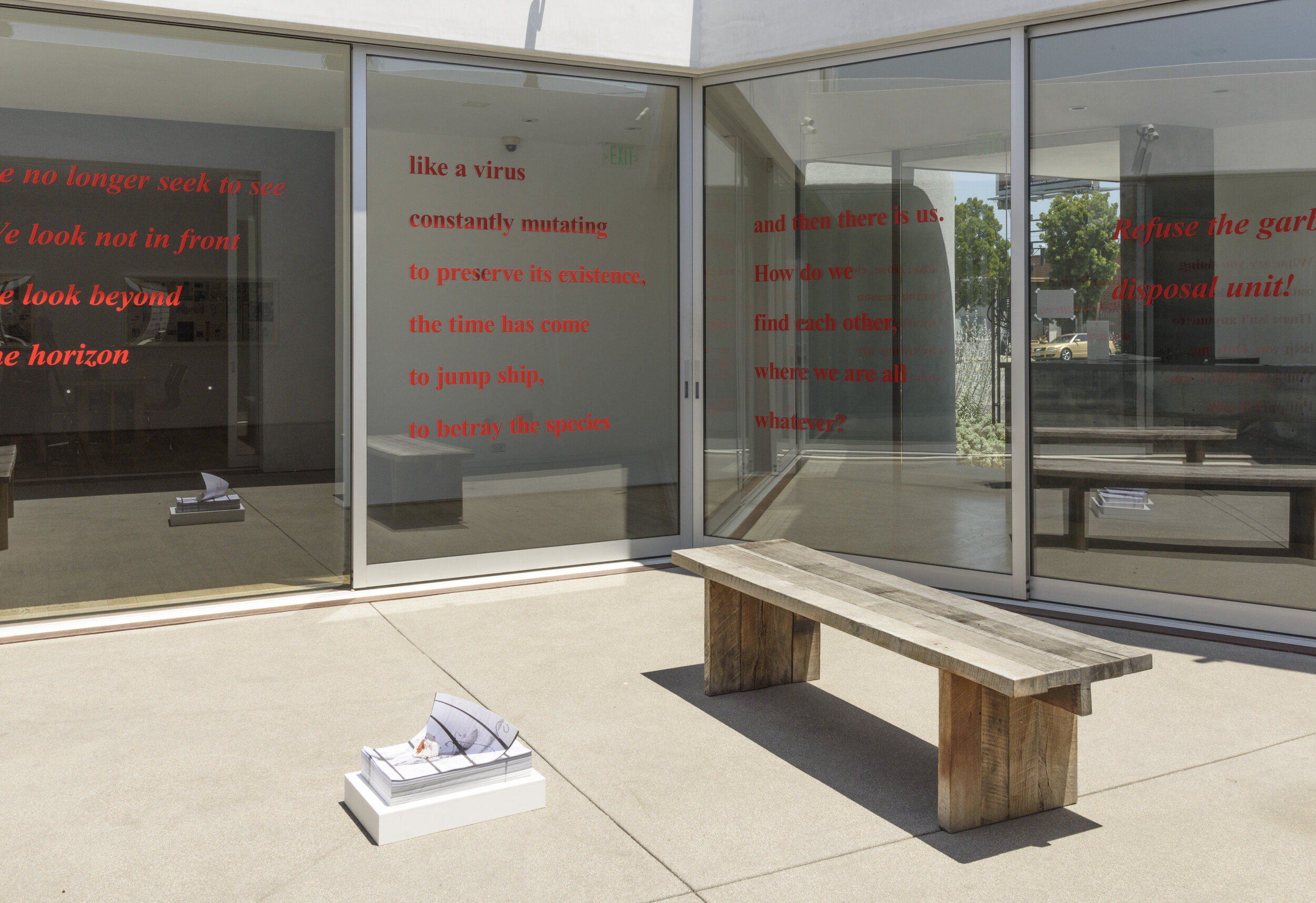

Occupying the central courtyard, Juan Capistran’s text installation creates a mash-up of ideas and language that can be entered at any point, literally and metaphorically. In This text is the beginning of a plan. See you soon!, Capistran blends material from William Golding's Lord of the Flies, Tiqqun’s Introduction to Civil War and This Is Not a Program to create a new conversation activated by the viewer at the center.

While Paratext is not a defined word in the dictionary, it is a term used by literary theorists to describe elements that frame the main text. The literary theorist Gérard Genette, quoting Philippe Lejeune, described it as “the fringe of the printed text which, in reality, controls the whole reading” - Genette, Gerard and Maclean, Marie. Introduction to the Paratext, New Literary History, Vol. 22 No.2, Probings: Art, Criticism, Genre (Spring 1991), pp 261.